What Is Rose Marie Berger Talking About in"Getting Our Gaze Back"?

Translating Women Back Into Scripture

A paradigm-shifting lectionary embraces the Bible's liberating power.

Illustration by Matt Chase

NEARLY 1.4 BILLION Christians around the world receive their weekly exposure to the Bible through a lectionary. In the U.S., as many as 60 percent of Christians attend services in churches that follow a lectionary. For many Christians, this is their only regular exposure to our faith's sacred narrative.

Even for those who love the ecumenical unifying energy of a common lectionary, we also acknowledge that the scripture snippets we hear on Sundays are chosen almost exclusively by Euro-Anglo male scholars, using Bible translations that reflect the same. (The translation committee for the 2011 Common English Bible was the first to include scholars of color.) It's hard to embrace the Bible's liberating power when you can't find yourself in the story, and it's even harder to show up when you learn you've been edited out of it.

Enter A Women's Lectionary for the Whole Church, by Wilda C. Gafney, a professor of Hebrew Bible, offering not only an entirely new Christian lectionary but also rigorous and fresh Bible translations that restore women and feminine references to scripture, as well as text notes and preaching prompts—all in accessible language.

Between Disaster and Paradise, a Motorcycle-Riding Monk Found His Way

His mortal remains are tucked in the earth—while his soul cracks jokes with the saints.

Illustration by Matt Chase

A MONK DIES much as he lived—in holy obscurity. That's the goal at least.

Father Maurice Flood lived as a Trappist for 64 years. At his funeral in August, his abbot described Maurice's monastic journey as "atypical." And so it was.

To enter the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance (Trappists), one vows silence, stability, poverty, chastity, continual conversion, and obedience to Christ (in the person of one's abbot). When I met Maurice in 1980, he was uproariously funny and riding his Harley-Davidson around the U.S. with a homemade telescope strapped to the side. Though neither silent nor "stable," his other vows appeared to hold firm.

Will the Equal Rights Amendment Threaten Religious Liberty?

Greater support for women and LGBTQ rights aligns with greater religious freedom protections. A study by Brian J. Grim at the Religious Freedom and Business Foundation found that "the average level of religious freedom is 36% higher in the countries with higher levels of support for LGBT rights than in countries with low levels of support for LGBT rights." The expansion of human rights is good for religious freedom. This shouldn't surprise us: A culture that values human rights for women and LGBTQ people will also value human rights for religious people.

What Otters Can Teach Us About Dismantling Empire

When empire is "game master," Jesus-followers should interrogate the "play."

Illustration by Matt Chase

TOURISTS SPOTTED OTTERS in the Potomac River this spring. Not unheard of, but rare.

North American river otters are the only otter species in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. For millennia they were an apex species that served as "doctors" for healthy ecosystems by maintaining population levels of fish, frogs, and insects. The Colonial-era transnational fur trade, and its modern-era descendants of land destruction and water pollution, brought otters to the brink of decimation.

Now the otters are returning, a signal that decades of reparatory work to protect the Chesapeake watershed is having modest success.

The word most associated with these agile water weasels is "play." Play is a fundamental way of interacting in the world; it's how creatures "practice into being" what we can only imagine at first. Play develops communal trust, agility, resilience, strength, and strategy—and situates the soul firmly in the individual and social body.

My Wife and I Married on the Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe

What if sexual identity holds a special place in the complex beauty of the natural order?

Illustration by Matt Chase

AT AGE 43, I found the person I wanted to marry. At 50, I proposed. And she said yes. I, a generations-long Roman Catholic, was proposing to a United Methodist (with deep ancestry in Presbyterianism). We wanted our marriage witnessed and blessed by the church. We wanted to hear our community pledge to uphold and care for us in marriage. But we were not of opposite genders—a prerequisite for marriage in both our denominations.

For seven years we prayed and wrestled over our "mixed marriage" and what to do with our respective denominations' position, which amounted to "love the sinner, hate the sin." The priests in our Catholic community recognized us as a couple and tended our wounds when anti-gay teaching came from the pulpit. But they could not invite us on couples' retreats, consecrate our marriage, or even offer us a blessing. Our evangelical and Methodist communities defended our civil rights, but not our ecclesial ones. If we asked for liturgical rites, we became a "problem."

Eventually, we found an Episcopal community that not only welcomed us but offered marriage preparation tailored for same-gender couples. We signed on the dotted line, completed the pastoral process, and sent out invitations for our April 2020 wedding. A global pandemic scuttled our plans.

The Lingering Trauma Of Mob Violence

Events like the Jan. 6 attack leave wounds to the soul and psyche.

Illustration by Matt Chase

FOR ME, FURY has a face. In 1999, I sat in a refugee camp with Kosovar families. They had been driven from their homes ahead of attacking Serb crowds aroused to violence by the cruel and charismatic oratory of then-president Slobodan Milosevic.

Thirty-year-old Hajrija thrust forward this question: "How can I live with this pain that our neighbors who we shared our bread with, who my husband shoveled snow from her walk even before he cleared our own ... asked aloud, in our yard while I was hanging my laundry, how she was going to kill me and my children? She was trying to decide between mortar or sniper. How can I go back and live with this person?" Hajrija was incandescent with fury.

On Jan. 6 this year, I saw the other side of Hajrija's story—the spectacle of an attacking crowd. Several thousand gathered in front of the White House under the sway of another cruel and charismatic president. Like all such leaders, he deceived the crowd by saying their sacred rights had been stolen; that the enemy wants to "indoctrinate" their children; that if they did not act, the enemy would "illegally take over our country." He loaded the crowd, aimed them at Congress—then gave the command.

It's Time to Be the Conscience of American Politics

President Joe Biden addresses the nation after his inauguration on Jan. 20, 2021. REUTERS/Joshua Roberts/Pool/File Photo

I believe fervently in the words of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who said that "the church is not called to be the master or servant of the state, but to be the conscience of the state." In that vein, we will be neither chaplain nor sycophant to our new political leaders. Instead, we seek to be a faithful conscience, serving as a bridge-builder and offering prophetic critique (and pressure) when necessary.

Praying With Jazz For Lent

"Is music pleasure, prayer, and praise in one?"

Illustration by Matt Chase

WHEN THE CHAOS gets too much, I listen to jazz. I'm not an aficionado. I just know that brave jazz refreshes my freedom. Lately, I've been listening to a lot of jazz.

The stay of execution offered by a COVID-19 vaccine allows for a giddy, perilous optimism. Even a minute crack in our coronavirus armor brings up emotions too dangerous, too chaotic to express: A trembling wave of the suffering we have endured, heavy across the shoulders like the splintery weight of the cross.

For ballast against overwhelming rage, I turn to The Five Quintets by poet Micheal O'Siadhail: "Be with me Madam Jazz I urge you now, / Riff in me so I can conjure how / You breathe in us more than we dare allow."

Who's at Fault? New Reports on Clergy Sex Abuse Offer Different Views

Former U.S. Cardinal Theodore Edgar McCarrick arrives for a meeting at the Vatican March 4, 2013. REUTERS/Max Rossi/

What the reports have in common is long lists of sexual abuse victims and their broken families. The testimonies of survivors are instructive for the quality of their demand for justice and yet, to paraphrase Tolstoy, each unhappy survivor story "is unhappy in its own way." Each story is unbearable in its details of the physical and psycho-spiritual torture and the chronic wounds that remain. But in other respects, the two reports could not be more different.

Fratelli Tutti: A Remix of Pope Francis' Greatest Hits

'We can only be saved together.'

Illustration by Matt Chase

Fratelli Tutti, Pope Francis' encyclical on "social friendship" released in October, sounds like a new gelato flavor—something between fior di latte and tutti frutti. Like the Italian frozen dessert, Francis' pastoral sections melt in your mouth—but a nutty, bitter crunch hides in every bite.

Encyclical letters are used by popes to address important issues. Recently, these letters have been addressed not only to Catholics, but to "all people of good will."

Where Laudato Si', released five years ago, developed new doctrine and broke ground in Catholic social teaching to address the fierce urgency of climate collapse, "On Universal Fraternity and Social Friendship" (as it's called in English) counsels us not to backslide as a human family. Cardinal Michael Czerny said, "If Laudato Si' taught us that every thing is connected, then Fratelli Tutti teaches us that everyone is connected."

We Can Help Prevent an Election Crisis. Here's How

Seven concrete steps to safeguard the integrity of the vote

A voting booth inside a fire station in the Coral Gables neighborhood during the Democratic presidential primary election in Miami. March 17, 2020. REUTERS/Marco Bello/File photo

1. Get involved

Scenario: Voting places are closed, and mail-in ballots are restricted because there are too few election workers due to COVID-19 concerns.

Tip: Democracy is a team sport. Everyone can be an election worker. Commit a certain number of people from your church to register as poll workers and mobilize medical personnel to speak on coronavirus-safe voting practices. The U.S. Election Assistance Commission hosts a video explainer and training information for each state, and you can support efforts to recruit young poll workers through powerthepolls.org.

'My Sixth Great-Grandfather Bought My Sixth Great-Grandmother'

Revisiting my entangled and complicit family history.

Illustration by Matt Chase

HOW CAN SOMEONEborn white take on new flesh when they are old?

This is the question I hear when I read the story of Nicodemus during this Black Lives Matter moment amid the 400-year-long freedom struggle of Black people in the U.S. "How can someone be born when they are old? Surely they cannot enter a second time into their mother's womb to be born!" (John 3:4). How?

In 1707, my sixth great-grandfather bought my sixth great-grandmother at a slave auction at a French military post in what is now Mobile, Ala. She, later "christened" Thérèse, was a 10-year-old Chitimacha girl. He, Jacques Guedon, was a 17-year-old from Nantes in Brittany who had been recruited into the French colonial navy.

The Chitimacha were the most powerful nation along the Gulf Coast. Prior to contact with Europeans, the Chitimacha lived in a sophisticated matrilineal culture of classes and clans that served them for more than 10,000 years—through disease, war, and climate changes. They vigorously and continually defended their homeland against incursions and slave raids by English, Spanish, and French military, migrants, and missionaries. Today, they are the only tribe in Louisiana to still occupy a portion of their aboriginal homeland.

But a young French-Canadian commander named Bienville was tasked with establishing a fort at Mobile and defending it against the English. He needed to make alliances with native nations—primarily the Chickasaw and Choctaw—or severely weaken those that refused. To accomplish these twin goals and build up his personal wealth by selling Indian slaves, Bienville led his regiment in a night raid on Thérèse's village. Likely all the adults were massacred. The dozen or so children left alive, including Thérèse, were rounded up for sale. It was a minor skirmish in France's half-hearted attempt to establish and maintain extractive trade routes for maximum profit and minimum outlay, an expedient conquest to boost political standing and pay off debts.

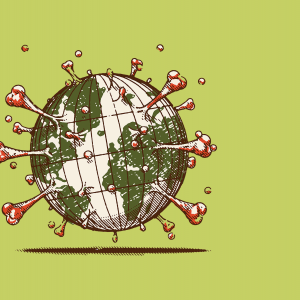

Christianity's First Pandemic Sounds Eerily Familiar

In the sixth century all worship was suspended, people hoarded, and survivors bore the economic burdens.

Illustration by Matt Chase

THE HORROR JOHN of Ephesus witnessed in north Africa and Constantinople was so traumatic that it took him three years before he could begin to tell the story.

"Thy judgments are like the great deep," prayed John of the "cruel scourge" that struck the whole world in 544 C.E., when the plague spread along the trade routes of Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. "Like the two edges of the reaper, it successively passed across the earth, and progressed without stopping," wrote John. The cities stank with unburied corpses. This sixth century deacon and hagiographer wrote, "The mercy of God showed itself everywhere toward the poor, for they died first while everyone was still healthy enough to ... carry them away and bury them."

No wonder John drew upon the psalms of lament and the "weeping prophet" Jeremiah for guidance. His congregation was dead or dispersed. To anoint and bury the dead meant contamination. All worship was suspended. The normally scrupulous were hoarding and stealing. And rulers who had overspent on imperial expansion placed impossible economic burdens on the survivors.

And then it all happened again 14 more times throughout north Africa—because pandemics recur in waves, sometimes for as long as 200 years.

What World is Possible After the Pandemic?

The coronavirus has forced a global sabbath. Will it also lead to a global Jubilee?

Illustration by Michael George Haddad

WE DON'T KNOW the full extent of the coronavirus pandemic. We know of the many who have died as a direct result of infection. We know that whole countries have turned on a dime to shield themselves from the shadow of death as it passes over. We don't know where it will lead.

In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, Rebecca Solnit wrote, "Horrible in itself, disaster is sometimes a door back into paradise, that paradise at least in which we are who we hope to be, do the work we desire, and are each our sister's and brother's keeper." Solnit reminds us that disasters and plagues sometimes signal liberation.

COVID-19 has forced the human community into mourning. In our retreat from the work-a-day world, it has imposed a global sabbath and Jubilee. Staring into this "cruel scourge," as John of Ephesus described the Justinian plague in the year 545 C.E., can we also see that another world is possible?

The Jubilee legislation found in Leviticus 25 lays out a vision for "social and economic reform unsurpassed in the ancient Near East," according to Robert K. Gnuse. The Jubilee laws declared that Yahweh was the rightful owner of all the earth, and therefore all Israelites—rich and poor—have an equal right to its abundance, within limits. In an economic system based on land and its produce, this was a radical transformation. The legislation undercut wealth disparities by preventing land speculation and by mandating debt forgiveness and interest-free loans. Finally, it ordered the release of the enslaved and those in debtors' prison.

There's Nothing Pro-Life About Trump

Trump's weaponization of whiteness and all-out assault on America's working poor stand in stark contradiction to the "culture of life" that Catholics embrace.

Illustration by Matt Chase

WHITE CHRISTIAN VOTERS —evangelicals, but also Catholics—pushed Trump over the finish line in the 2016 election. Trump regularly holds court in the media with evangelicals but has been less overt with Catholics. That is until January, when he favored some with a personal appearance at the annual March for Life on the national Mall, held in protest of the 1973 Supreme Court decision that overturned state bans on abortion.

"Catholics were of secondary importance to the Trump campaign in 2016, behind evangelicals. That hasn't changed, but there is at least an effort to reach this community now," former Rep. Tim Huelskamp (R-Kan.) told Politico in January.

As a Catholic, I'm deeply troubled by this president. Trump stands against everything I've been taught to believe.

Pope Francis has prioritized the climate crisis for Catholics; Trump withdrew from the Paris accords and dismantled the modest advances made under Obama.

Pope Francis says welcoming migrants builds a strong social ethic; Trump implements policies that tear apart families and imprison migrant children.

Catholics believe in promoting a consistent moral stance that allows life to flourish. Under the Trump administration average life expectancy in the U.S. has been on the decline for three consecutive years (representing the longest consecutive decline in the American lifespan since World War I).

Pope Francis teaches that the death penalty is no longer permissible under any circumstance; Trump's attorney general reinstated the federal death penalty, executing prisoners for the first time in nearly two decades.

The Gospel According to a TikTok Evangelist

Be fierce, creative, and practical in your desire to do good.

Illustration by Matt Chase

IF JESUS BROUGHT good news to the poor today, it might look like one of Shaunna Burns' videos.

Burns is an honest-to-God evangelist on TikTok, the fast-growing, Chinese-owned, short-form video-sharing social network. Translate Jesus' "brood of vipers" and "whitewashed tombs" into f-bombs and salty vernacular and you get Burns' practical "good news" that's changing lives.

A former debt collector, Burns knows all about the shady practices of collection agencies. But she didn't start her 60-second "debt pro tips" on TikTok until she got a call herself from a collection agency harassing her for her daughter's medical bills.

"Hey, guys. So, here's some quick debt-collection pro tips," North Carolina-based Burns starts in her first video in December. She then instructs the uninformed: It's illegal for debt collectors to call outside of certain hours. Medical debt has a statute of limitations—usually three to six years—that varies by state. Always ask a collector for a copy of your original signed invoice.

Will We See Through the 'Fog of War' This Time?

Burning debris are seen on a road near Baghdad International Airport, which according to Iraqi paramilitary groups were caused by three rockets hitting the airport in Iraq, Jan. 3, 2020, in this image obtained via social media. Iraqi Security Media Cell via REUTERS

The attack by a U.S. MQ-9 Reaper drone that fired missiles into a convoy carrying Soleimani was neither impulsive nor a retaliatory response. It was not undertaken to protect Americans. It was not an act of patriotism. It was not done to defend the U.S. embassy in Baghdad after the "dramatic but bloodless" siege. If anything, it was in response to Trump's increasingly untenable situation at home.

Did Pope Francis Just Elevate These Anti-Nuclear Activists to Religious Prisoners of Conscience?

Pope Francis speaks during a news conference onboard the papal plane on his flight back from a trip to Thailand and Japan, Nov. 26, 2019. REUTERS/Remo Casilli/Pool

Two years after the Vatican State signed the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (currently ratified by 34 countries), he declared during an in-flight press briefing from Japan to Rome, "Not only their use, but also possessing them: because an accident or the madness of some government leader, one person's madness can destroy humanity."

Epiphany is a Time for Imaginative Leaps

Paradigm shifts begin with a daring political act.

Illustration by Matt Chase

IMAGINE YOURSELF IN a darkened theater. At center stage sits a woman, child on her lap, both wrapped in tonal greys. A tiny stream of light falls from above. Off left, large animals shift their weight on floorboards, chuff-chuffing their breath; foreign tongues murmur them calm. Off right, the only sound is of metal rasps running repeatedly down the length of blades; random sparks flare off the cutting teeth. This is Epiphany. Everything is waiting to happen. We know the narrative detail: Mary and Jesus, a manger, the Magi's star-trekking journey with camels and gifts to honor a "newborn king" (while Herod, like Pharaoh, plots a bloody offense). But Epiphany is a season for paradigm shifts. What if we scramble the details? Imagine this. Off left, the chuff-chuffing of foreign tongues come not from men calming beasts, but camels praying as they approach the child, the spiritual waterhole for the world. The camels have not brought kings or astrologers, but a guild of bakers, who extend platters of fresh bread toward the child. At center, the woman wrapped in a cloak of ultraviolet leans back on her stool: She has given birth to a star, filling them both with light. At her side stands a human child. He gazes off right. The sound of rasps and swords, boots and shouted commands fascinate him. Slowly, the child lets go his mother's hand, relaxes his throat muscles, measures his breath. In a world of bread and circuses, he has made brothers of soldiers. He is a sword-swallower and eats their pain.

I Prayed The Rosary for Immigrant Children; I Was Arrested

Immoral legislation calls for our dignified rage.

Illustration by Matt Chase

"NO" IS A COMPLETE SENTENCE. I said it recently to a U.S. Capitol Police officer when he asked me to stop praying the rosary for immigrant children and to move. He then arrested me for "crowding, obstructing, or incommoding" in the rotunda of the Russell Senate Office Building in D.C.

That day the police arrested 71 Catholics. In the parlance of Christian nonviolence, we brought the spiritual power of our prayer to a site of mortal sin—specifically the offices of powerful lawmakers who support, through cowardly and often deliberate consent, caging immigrant children. The border patrol apprehended 69,157 such children at the U.S.-Mexico boundary between October 2018 and July 2019, seven of whom have died after being in federal custody.

What is the significance of Catholics and other Christians saying "no"? At its most authentic, religious faith builds moral muscles that push the human species to become more generous and just and guard against it backsliding into barbarity. While shallow religion shapes people for instinctive compliance to authority, ecclesial and secular, a deep faith tradition trains for moral discernment and formation of conscience and provides a narrative for how to resist immoral actions.

What Is Rose Marie Berger Talking About in"Getting Our Gaze Back"?

Source: https://sojo.net/biography/rose-marie-berger